Photo by Tomas Jasovsky on Unsplash

My son Tony was born at five years old by jumping out of my shirt.

Tony was two when he came into my home from foster care. I was a licensed foster mom and had already adopted a little girl from the system. But Tony was not ready for love. He was too angry, too hurt by all that had happened to him.

Instead, he raged.

He trashed his room. He bit me. He had terrors that left both of us demolished. He stood in the middle of his room and screamed.

“He’s afraid we’re going to give him back,” said his new big sister.

“We’re not,” I said.

What does it mean to be born?

In our culture, it is vaginal birth: the baby coming from the canal, wet with life itself. It is a swoop of air on lungs not yet imprinted with the sweet coolness of oxygen. It is from water to air—from the ocean of the womb to the sparkling sky.

Or it can be the spiritual birth of many religions. The baptism, the awakening. It is the epiphany of the atheist who realizes that existentialism includes joy, or the duty bound to the ordinary rigors of their faith.

Lastly, there is the birth of dying — the advent to heaven, or a spiritual plain, or just release and unknowingness. In our society, we recognize that death is a birth of itself. A person is gone, and the new life is what remains.

But seldom do we recognize the birth of love.

Each moment we live is an opportunity, a birth in and of itself. We turn our eyes to the world, and we breathe its air, and we know we belong—somewhere.

Everything I did centered on helping Tony, from keeping him wrapped up in predictable structure to facilitating visits with his other mother, because love is not a contest or competition. Everyone deserves healing. As our family saying evolved: no one gets left behind.

Tony learned age-appropriate skills—almost ferociously like he was an animal who had to survive. I woke in the middle of the night to find him standing on the kitchen table, a paring knife in one hand, an apple in the other. Tony was going to take care of himself.

But truly letting me in? Not happening.

I cried in the bathroom when he still raged, bewildered at my own feelings. Did I truly love Tony? There were times I felt so lost. I began to realize how much his anger reminded me of my pain, from a childhood of abuse.

They say you have to love yourself before you can love others. I am here to say that is not true.

I loved my children long before I could love myself.

So I started saying it all the time. “I love you,” I told Tony when he broke every toy in his room. “I love you,” I said when he ripped down the curtains and then punched me. “I love you,” when I had to restrain him, rocking and singing, tears on my cheeks.

By learning to love Tony in his rages, I finally gave myself permission. It was okay to be angry. It is okay to have rage against a world that has betrayed you.

After work, school, and therapy, our nightly routine was dinner, then storytime. Every night we finished with Goodnight Moon and then walked outside in our jammies to wave goodnight to the moon itself.

We were poor, but the kids didn’t know it. They thought the shabby toys from the thrift store were filled with magic. They had a safe bed every night and a sky filled with majesty.

“The moon will never go away,” I told them as we waved.

It was Tony who turned his alert, watchful face to me. “Like you,” he said.

“Like me,” I answered. “Like us. You too.”

I could tell he thought about that for the longest time.

You Might Also Like: Sitting With Anxiety: How Trauma & Stigma Impact Everyday Life

One day Tony wanted me to climb under my shirt. I put my arms under his weight and carried him around the house, as he nestled against my bare skin. He was a big boy now, almost five years old. His feet hung from under the shirt.

“Take me outside,” he said, his voice muffled.

I carried him outside, holding him under the fabric. “Walk me up and down the street,” he said.

I did.

“Tell everyone you are going to have a baby.”

I walked past our neighbors, out gardening on this beautiful spring evening.

“Guess what!” I announced. “I’m having a baby!”

Bless their souls, they responded well. “Oh, that’s great news!” They shouted back.

It became our tradition. I wore a big tee-shirt, and Tony climbed up underneath. His big sister walked proudly next to us.

“Guess what?” I called. All the neighbors came to know this game. “I’m so happy for you,” they called back when I announced my news.

When we got back home, Tony jumped out of my shirt. “I’m here!” he cried, his cheeks flushed pink with pleasure.

“You’re here!” I clapped for joy.

Was it that day Tony was born into love? It was probably one of hundreds. Thousands.

Each moment we live is an opportunity, a birth in and of itself. We turn our eyes to the world, and we breathe its air, and we know we belong—somewhere. We just have to find that place. It is the gift we can give each other.

Tony is a young man now, successful by any cultural indicator. He’s got a wonderful job and life. He permitted me to write this. I waited twenty years before writing anything about my now-adult children and only do so with their consent. I do not share their private stories of why they entered foster care, or their trauma histories. Those are their stories to tell, not mine.

What I am struck my most are his eyes when Tony stops by to visit me, unexpected, in the evenings. The way he walks in the door, as alert as ever, his body leaning slightly forward. I see the little boy on the kitchen table, holding his knife. I see the toddler raging. I see him jumping from my shirt, and all the times that came after.

“There’s my mama,” he says, his face lighting up, and I know he has arrived.

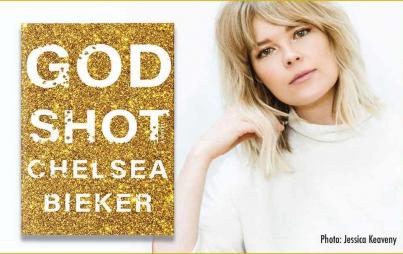

Rene Denfeld is the author of The Butterfly Girl, out now from Harper.

Related: